Blocked Cats are an Emergency

Tony Johnson, DVM, DACVECC

Date Published: 10/02/2014

Date Reviewed/Revised: 06/01/2022

When something happens to stem the flow of a cat's urine, trouble ensues - and fast.

Urine has lots of good things in it. In many cases, they are substances that cats or people can’t live without, such as potassium, sodium, and water. The kidneys sense and adjust the composition of bodily fluids and drop the excess into the urine. If a person eats a large order of fries, covered with salt, the kidneys dump the unwanted excess of sodium into the urine. The same is true with many other substances, like water, that need to be regulated. Urine is (usually) sterile, so unless there is a urinary tract infection, urine is pure. It’s not the terrible stuff that many third graders make it out to be. True, it does have the waste products of metabolism in it, which a body needs to remove.

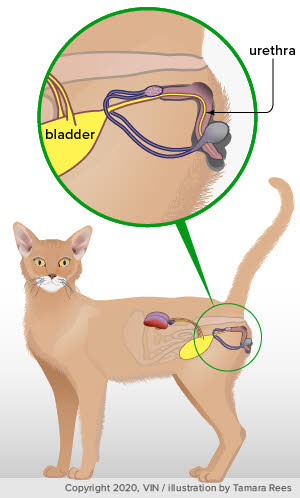

And that’s where some of the problems begin. If the flow of urine stops, those waste products build up and negatively impact the way the body works. One of the most common ways that happens is when a cat’s urethra (the tube that carries urine from the bladder to the litter box) gets blocked. Known in veterinary parlance as a ‘blocked cat’ or ‘blocked tom,’ this poorly understood disorder is seen with alarming frequency in veterinary hospitals and ERs.

Many ERs see about two to three cats per week who cannot urinate. Cats can be in all stages of the disease, from the early onset ones who just seem a little painful and have a big, hard bladder to the nearly dead ones that are in many cases beyond saving.

The actual plug that stops the flow can be made of bladder stones (often erroneously called kidney stones), tumors or a gooey mix of mucus and protein known as ‘matrix’ that has the consistency of toothpaste. How and why matrix forms, no one knows, despite a few decades of investigation. Adding to the confusion, the name of the disorder has changed no less than four times in the past 20 years from feline lower urinary tract disorder (FLUTD) to feline urologic disorder (FUS) to feline interstitial cystitis (FIC) to the most recent iteration of Pandora Syndrome, which hasn’t really caught on yet.

The causes go beyond a mucousy plug, as well. A host of other factors, such as stress, lack of access to water, diet, infectious agents, indoor lifestyle, and many other causes have been implicated as being responsible for the lead-up to getting blocked. Those little plugs don’t form in a vacuum: something causes them to form, and we don’t know with any certainty what factors contribute to it.

Cats that are blocked often show the following signs:

In advanced cases, where the urine flow has been stopped for more than 24 hours, cats can become systemically ill from retained toxins and start vomiting, or become very weak and lethargic. Death usually happens within 48 hours, and it’s not a pleasant way to go. The pain with this disease is immense, and some cat owners understandably choose euthanasia over trying to reestablish the flow of urine.

The course after unblocking these cats is just as unpredictable and mysterious as the factors leading up to the obstruction; some cats are released from the hospital never to suffer another episode, while others will have repeated occurrences days, weeks or years later. This is an inhumane disease.

Managing these cases medically can go way beyond relieving the obstruction in some cases. First priority is fixing the plumbing problem: getting urine to flow. This is usually done with anesthesia and a catheter to remove the obstruction. Managing the havoc wreaked by the toxins is next. This can necessitate some medical dancing as veterinarians try to put things back in place. Disorders of deadly potassium, elevated renal values, and severe dehydration can mean days in the hospital, even long after the urine is flowing again. It can get complex, expensive, and can wear down even the most committed of owners for the really medically complex (and expensive) ones.

However, getting the urine to flow and taking the cat home is the easy part. After this episode, lifestyle changes are necessary: medication tweaks, medical rechecks, and diet changes that try to extend the initial complexity of this disease across months or years.

Compared to 20 years ago, cats with this disease do go home and get better, even some of the tough cases. Someday, science will provide an answer and veterinarians will have some means to prevent this disease in the first place, or some surefire way to treat it. Until then, rush your cat in to be seen if you see the signs.

Tony Johnson, DVM, DACVECC

Date Published: 10/02/2014

Date Reviewed/Revised: 06/01/2022

When something happens to stem the flow of a cat's urine, trouble ensues - and fast.

Urine has lots of good things in it. In many cases, they are substances that cats or people can’t live without, such as potassium, sodium, and water. The kidneys sense and adjust the composition of bodily fluids and drop the excess into the urine. If a person eats a large order of fries, covered with salt, the kidneys dump the unwanted excess of sodium into the urine. The same is true with many other substances, like water, that need to be regulated. Urine is (usually) sterile, so unless there is a urinary tract infection, urine is pure. It’s not the terrible stuff that many third graders make it out to be. True, it does have the waste products of metabolism in it, which a body needs to remove.

And that’s where some of the problems begin. If the flow of urine stops, those waste products build up and negatively impact the way the body works. One of the most common ways that happens is when a cat’s urethra (the tube that carries urine from the bladder to the litter box) gets blocked. Known in veterinary parlance as a ‘blocked cat’ or ‘blocked tom,’ this poorly understood disorder is seen with alarming frequency in veterinary hospitals and ERs.

Many ERs see about two to three cats per week who cannot urinate. Cats can be in all stages of the disease, from the early onset ones who just seem a little painful and have a big, hard bladder to the nearly dead ones that are in many cases beyond saving.

The actual plug that stops the flow can be made of bladder stones (often erroneously called kidney stones), tumors or a gooey mix of mucus and protein known as ‘matrix’ that has the consistency of toothpaste. How and why matrix forms, no one knows, despite a few decades of investigation. Adding to the confusion, the name of the disorder has changed no less than four times in the past 20 years from feline lower urinary tract disorder (FLUTD) to feline urologic disorder (FUS) to feline interstitial cystitis (FIC) to the most recent iteration of Pandora Syndrome, which hasn’t really caught on yet.

The causes go beyond a mucousy plug, as well. A host of other factors, such as stress, lack of access to water, diet, infectious agents, indoor lifestyle, and many other causes have been implicated as being responsible for the lead-up to getting blocked. Those little plugs don’t form in a vacuum: something causes them to form, and we don’t know with any certainty what factors contribute to it.

Cats that are blocked often show the following signs:

- Straining repeatedly in the litter box (often mistaken for constipation)

- Crying or howling

- Licking at the genitals/below the base of the tail

- Hiding

In advanced cases, where the urine flow has been stopped for more than 24 hours, cats can become systemically ill from retained toxins and start vomiting, or become very weak and lethargic. Death usually happens within 48 hours, and it’s not a pleasant way to go. The pain with this disease is immense, and some cat owners understandably choose euthanasia over trying to reestablish the flow of urine.

The course after unblocking these cats is just as unpredictable and mysterious as the factors leading up to the obstruction; some cats are released from the hospital never to suffer another episode, while others will have repeated occurrences days, weeks or years later. This is an inhumane disease.

Managing these cases medically can go way beyond relieving the obstruction in some cases. First priority is fixing the plumbing problem: getting urine to flow. This is usually done with anesthesia and a catheter to remove the obstruction. Managing the havoc wreaked by the toxins is next. This can necessitate some medical dancing as veterinarians try to put things back in place. Disorders of deadly potassium, elevated renal values, and severe dehydration can mean days in the hospital, even long after the urine is flowing again. It can get complex, expensive, and can wear down even the most committed of owners for the really medically complex (and expensive) ones.

However, getting the urine to flow and taking the cat home is the easy part. After this episode, lifestyle changes are necessary: medication tweaks, medical rechecks, and diet changes that try to extend the initial complexity of this disease across months or years.

Compared to 20 years ago, cats with this disease do go home and get better, even some of the tough cases. Someday, science will provide an answer and veterinarians will have some means to prevent this disease in the first place, or some surefire way to treat it. Until then, rush your cat in to be seen if you see the signs.

Urinary Blockage in Cats

Wendy Brooks, DVM, DABVP

Date Published: 06/04/2002

Date Reviewed/Revised: 07/12/2022

Additional Resources

Recognizing the Emergency

We have already described the signs of feline idiopathic cystitis (F.I.C.) as straining to urinate, bloody urine, etc. If the cat is a male, he is at risk for an especially life-threatening complication of this syndrome: the urinary blockage.

Mucus, crystals and even tiny bladder stones can clump together to form a plug in the narrow male cat urethra. The opening is so small that it does not take a lot to completely or even partially obstruct urine flow. Only a few drops of urine are produced or sometimes no urine at all is produced.

It is hard to tell when a cat is blocked as the inflammation, urgency, and non-productive straining also accompany cystitis whether or not there is a blockage. The easiest way to tell is by feeling in the belly for a distended bladder. It is often the size of a peach and if there is an obstruction the bladder will be about as hard and firm as a peach. (Normal bladders are usually soft, like partly filled water balloons, and non-obstructed inflamed bladders are usually very small or empty). Still, while this size and texture difference is obvious to the veterinarian, most pet owners are not able to feel for the bladder correctly. If there is any question about whether a male cat is blocked, he should be taken to the vet for evaluation as soon as possible.

If the blockage persists for longer than 24 hours, urinary toxins will have started to build up in the system. Do not put off having the cat checked!

Confirmation and Assessment

Bladder Palpation by Veterinarian

The veterinarian will feel the bladder in the abdomen and attempt to express urine. Sometimes gentle pressure will actually expel the obstruction, but usually the cat will require more aggressive means of relief. The blocked cat will be assessed for dehydration and toxin buildup. The urinary toxins that build up in obstructions commonly cause vomiting, nausea, and appetite loss. They can also cause life-threatening heart rhythm disturbances. Your cat is assessed for all these complications as they will need to be addressed.

A partial blockage can be just as serious as a complete blockage. Treatment is usually the same.

If the blockage persists for 3 to 6 days, the toxin build-up will result in death.

Initial Treatment

Urinary Catheterization of the Penis

The single most important thing for the obstructed cat is to have the blockage relieved. This is done by placing a urinary catheter through the urethral opening and either through the obstruction itself or using pulses of flushing solution to move the plug back into the bladder, where it can be dissolved. This procedure is often painful, and sedation will most likely be needed. Some cats are unblocked with great difficulty only. Some cats cannot be unblocked and must have an emergency perineal urethrostomy to re-establish urine flow (see below for details on this surgery).

Fortunately, most cats are successfully unblocked. The urinary catheter is sewn in place and will stay in place for a couple of days. Often a urinary collection bag is attached to the catheter so that urine production can be measured. Sometimes, the bladder is filled with sterile fluid and flushed out to remove crystals, inflammatory debris, and blood.

When the blocked cat has filled his bladder to capacity, his kidneys stop making urine as there is nowhere for it to go. Once urine flow returns, the kidneys quickly begin to correct the metabolic disasters that have been taking place. Often an extremely sick blocked cat can be snatched from the jaws of death by having proper fluid support and by re-establishing urine production. It is amazing how efficient the working kidneys can be in restoring the body's balance; still, it is important to realize that this is a serious condition, and not every cat can be saved.

Occasionally a cat is brought in soon after blocking and achieves an excellent urinary stream immediately after unblocking. These cats may be able to proceed with treatment without having to spend a few days in the hospital or without having to have the catheter sewn into place. Most blocked cats do not fit into this category, but its important to realize that some cats are able to avoid more aggressive treatment.

Further, in the event of extreme budget limitations on the owner's part, a blocked cat can be unblocked quickly and returned to the owner for aftercare. This speed is not a good idea as the cat is likely to need additional support for the best chance of survival; still, given that leaving the cat blocked would be cruel and ultimately end in the cat's death, this may be an alternative in some cases.

What Happens During Hospitalization?

The kidneys do most of the work during the recovery phase. The cat must wear a type of collar that prevents biting at or removing the crucial urinary catheter. Urine production is monitored closely as after the obstruction is relieved, often dramatic urine volumes are produced. (This is called post-obstructive diuresis, and if the cat is not drinking on his own, it is vital that his fluid therapy matches the volumes produced as urine. If they do not, he will dehydrate.) Fluid therapy is given either intravenously or under the skin, depending on the degree of support needed by the cat. Medications are given to relieve pain and relax the irritated urethra.

After a couple of days of catheterization, the catheter is removed, and the patient is observed for re-blockage. He will not be allowed to go home until his urine stream seems strong and relatively easy. Some cats will leak urine at this point as it is painful for them to engage in normal pushing; this is generally a temporary problem. Once he seems to be urinating reliably on his own, he will be released for home care.

What to Watch for at Home after Discharge from the Hospital

In an ideal world, owners can learn how to feel the abdomen for a firm, obstructed bladder. This is hard to teach at discharge, mostly because, at this point, the cat is pretty sore. There will usually be medications and dietary recommendations to go home with the cat.

It is crucial to realize that the cat is at risk for re-blocking for a good week or two from the time of discharge. This is because the irritation syndrome that led to blocking in the first place is still continuing, and as long as the episode continues, blocking is a possibility.

At home, the same straining and possibly bloody urinewill still be produced. It is important for the owner to be aware of urine volume being produced and of bladder size, if possible. Any loss of appetite or vomiting should be reported to the veterinarian at once. If there is any concern about reblocking, the veterinarian can determine fairly easily if the cat has re-blocked even if the pet owner cannot.

Most cats recover uneventfully. Some cats, especially if they have been blocked before, will require ongoing preventative treatment.

Occasionally the bladder over-stretches while it is blocked and is permanently damaged. Such cats require medication to help them contract and empty their bladders normally. This is unusual, but one should be aware of the possibility.

Feline male anatomy

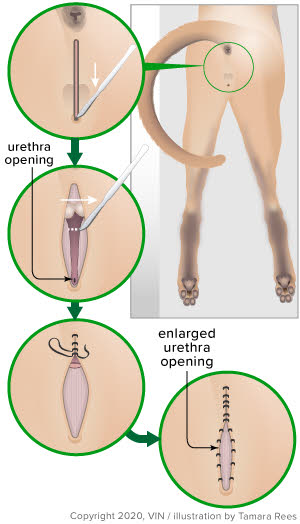

The Perineal Urethrostomy

Urinary blockage is almost exclusively a problem reserved for males. This is because the female urethra is shorter and broader and thus far more difficult to obstruct. When urinary blockage becomes recurrent in a male cat, it becomes time to consider surgical reconstruction of the genitalia to create a more female-like opening. This surgery is called the perineal urethrostomy or PU for short. Basically, the penis is removed, and a new urinary opening is made.

Before considering this surgery, here are some considerations:

What You Need to Know if you are Considering this Procedure for your Cat

Wendy Brooks, DVM, DABVP

Date Published: 06/04/2002

Date Reviewed/Revised: 07/12/2022

Additional Resources

- Lower Urinary Tract Disease in Cats

- Idiopathic Cystitis in Cats

- Inappropriate Elimination (House-Soiling) in Cats

Recognizing the Emergency

We have already described the signs of feline idiopathic cystitis (F.I.C.) as straining to urinate, bloody urine, etc. If the cat is a male, he is at risk for an especially life-threatening complication of this syndrome: the urinary blockage.

Mucus, crystals and even tiny bladder stones can clump together to form a plug in the narrow male cat urethra. The opening is so small that it does not take a lot to completely or even partially obstruct urine flow. Only a few drops of urine are produced or sometimes no urine at all is produced.

It is hard to tell when a cat is blocked as the inflammation, urgency, and non-productive straining also accompany cystitis whether or not there is a blockage. The easiest way to tell is by feeling in the belly for a distended bladder. It is often the size of a peach and if there is an obstruction the bladder will be about as hard and firm as a peach. (Normal bladders are usually soft, like partly filled water balloons, and non-obstructed inflamed bladders are usually very small or empty). Still, while this size and texture difference is obvious to the veterinarian, most pet owners are not able to feel for the bladder correctly. If there is any question about whether a male cat is blocked, he should be taken to the vet for evaluation as soon as possible.

If the blockage persists for longer than 24 hours, urinary toxins will have started to build up in the system. Do not put off having the cat checked!

Confirmation and Assessment

Bladder Palpation by Veterinarian

The veterinarian will feel the bladder in the abdomen and attempt to express urine. Sometimes gentle pressure will actually expel the obstruction, but usually the cat will require more aggressive means of relief. The blocked cat will be assessed for dehydration and toxin buildup. The urinary toxins that build up in obstructions commonly cause vomiting, nausea, and appetite loss. They can also cause life-threatening heart rhythm disturbances. Your cat is assessed for all these complications as they will need to be addressed.

A partial blockage can be just as serious as a complete blockage. Treatment is usually the same.

If the blockage persists for 3 to 6 days, the toxin build-up will result in death.

Initial Treatment

Urinary Catheterization of the Penis

The single most important thing for the obstructed cat is to have the blockage relieved. This is done by placing a urinary catheter through the urethral opening and either through the obstruction itself or using pulses of flushing solution to move the plug back into the bladder, where it can be dissolved. This procedure is often painful, and sedation will most likely be needed. Some cats are unblocked with great difficulty only. Some cats cannot be unblocked and must have an emergency perineal urethrostomy to re-establish urine flow (see below for details on this surgery).

Fortunately, most cats are successfully unblocked. The urinary catheter is sewn in place and will stay in place for a couple of days. Often a urinary collection bag is attached to the catheter so that urine production can be measured. Sometimes, the bladder is filled with sterile fluid and flushed out to remove crystals, inflammatory debris, and blood.

When the blocked cat has filled his bladder to capacity, his kidneys stop making urine as there is nowhere for it to go. Once urine flow returns, the kidneys quickly begin to correct the metabolic disasters that have been taking place. Often an extremely sick blocked cat can be snatched from the jaws of death by having proper fluid support and by re-establishing urine production. It is amazing how efficient the working kidneys can be in restoring the body's balance; still, it is important to realize that this is a serious condition, and not every cat can be saved.

Occasionally a cat is brought in soon after blocking and achieves an excellent urinary stream immediately after unblocking. These cats may be able to proceed with treatment without having to spend a few days in the hospital or without having to have the catheter sewn into place. Most blocked cats do not fit into this category, but its important to realize that some cats are able to avoid more aggressive treatment.

Further, in the event of extreme budget limitations on the owner's part, a blocked cat can be unblocked quickly and returned to the owner for aftercare. This speed is not a good idea as the cat is likely to need additional support for the best chance of survival; still, given that leaving the cat blocked would be cruel and ultimately end in the cat's death, this may be an alternative in some cases.

What Happens During Hospitalization?

The kidneys do most of the work during the recovery phase. The cat must wear a type of collar that prevents biting at or removing the crucial urinary catheter. Urine production is monitored closely as after the obstruction is relieved, often dramatic urine volumes are produced. (This is called post-obstructive diuresis, and if the cat is not drinking on his own, it is vital that his fluid therapy matches the volumes produced as urine. If they do not, he will dehydrate.) Fluid therapy is given either intravenously or under the skin, depending on the degree of support needed by the cat. Medications are given to relieve pain and relax the irritated urethra.

After a couple of days of catheterization, the catheter is removed, and the patient is observed for re-blockage. He will not be allowed to go home until his urine stream seems strong and relatively easy. Some cats will leak urine at this point as it is painful for them to engage in normal pushing; this is generally a temporary problem. Once he seems to be urinating reliably on his own, he will be released for home care.

What to Watch for at Home after Discharge from the Hospital

In an ideal world, owners can learn how to feel the abdomen for a firm, obstructed bladder. This is hard to teach at discharge, mostly because, at this point, the cat is pretty sore. There will usually be medications and dietary recommendations to go home with the cat.

It is crucial to realize that the cat is at risk for re-blocking for a good week or two from the time of discharge. This is because the irritation syndrome that led to blocking in the first place is still continuing, and as long as the episode continues, blocking is a possibility.

At home, the same straining and possibly bloody urinewill still be produced. It is important for the owner to be aware of urine volume being produced and of bladder size, if possible. Any loss of appetite or vomiting should be reported to the veterinarian at once. If there is any concern about reblocking, the veterinarian can determine fairly easily if the cat has re-blocked even if the pet owner cannot.

Most cats recover uneventfully. Some cats, especially if they have been blocked before, will require ongoing preventative treatment.

Occasionally the bladder over-stretches while it is blocked and is permanently damaged. Such cats require medication to help them contract and empty their bladders normally. This is unusual, but one should be aware of the possibility.

Feline male anatomy

The Perineal Urethrostomy

Urinary blockage is almost exclusively a problem reserved for males. This is because the female urethra is shorter and broader and thus far more difficult to obstruct. When urinary blockage becomes recurrent in a male cat, it becomes time to consider surgical reconstruction of the genitalia to create a more female-like opening. This surgery is called the perineal urethrostomy or PU for short. Basically, the penis is removed, and a new urinary opening is made.

Before considering this surgery, here are some considerations:

- This surgery is done to prevent obstruction of the urinary tract. It does not prevent feline idiopathic cystitis. This means the cat is likely to continue to periodically experience recurring bloody urine, straining, etc. He just will not be able to block and complicate the situation.

- Cats with perineal urethrostomies are predisposed to bladder infections and infection-related bladder stones. The University of Minnesota currently recommends that male cats with perineal urethrostomies have regular periodic urine cultures, even if they are asymptomatic. Expect a general schedule for your cat to have screening urine cultures at your veterinarian's office.

What You Need to Know if you are Considering this Procedure for your Cat

- The metabolic complications from the urinary blockage should be resolved before the surgery is performed. In some emergency situations this is not possible (the male cat cannot always be unblocked with a urinary catheter and a new urinary opening may have to be constructed on an emergency basis.) Residual urinary toxin build up is an important risk factor that should be eliminated or minimized if possible.

- Shredded paper or pelleted newspaper litter should be used during the 10 days following surgery. Clay and sand litter may stick to the incision and disrupt healing.

- The most serious complication that can occur post-operatively is scar (stricture) formation. This causes a narrowing of the urinary opening and the surgery may have to be revised.

- In theory, local nerve damage can occur during the surgery leading to urinary and/or fecal incontinence. Obviously these are disasters for a household pet but fortunately this is a very rare complication.

- As mentioned, regular urine cultures are recommended for cats with perineal urethrostomies.